Search london history from Roman times to modern day

196

Such is the history of London from the beginning of the seventh century to the third quarter of the eleventh century. We have next to consider—

1. The appearance of the town and the nature of the buildings.

2. The trade of the town.

3. The religious foundations.

4. The temporal government.

5. The manners and customs of the people.

197

I. he Appearance of the Town

If there had been any persons living to remember Augusta when the army of King Alfred took possession of the place, then, indeed, they would have shed tears, while standing on the rickety wooden bridge, to behold the shrunken and mean town which had taken the place of that stately City: to consider the ruins of noble houses; to see how trees grew upon the crumbling wall; to mark how great gaps showed the site of City gates; how broad stretches of ground lay waste, where once had stood the Roman villas. After a year or two, when the wall was repaired, and people flocked again to the “mart of all nations,” the aspect of the City improved. The stones of old erections—those above ground—had been used to repair the City wall; new gates had been built and the old gates had been restored; the quay was once more covered with merchandise, and the river was again filled with shipping—among the vessels was the king’s fleet maintained to keep off the Danes. The town behind the quays was rebuilt of wood—within two hundred years it was five times either wholly, or in great part, destroyed by fire. There were no palaces or great198 houses; some few had the great hall for the living-room and for the sleeping-room of servants and children, with the “Solar” or the chamber of the lord and lady, the Lady’s Bower, and the kitchens (see also p. 224).

After the time of Alfred, London rapidly advanced in prosperity and wealth. The restoration of the wall was recognised as an outward and visible sign of the security enjoyed by those who slept within it: trade increased; the wealth of the people increased; their numbers increased, because they were safe. Stone buildings began to be erected, and the outward signs of prosperity appeared. London threw out long arms within her walls. The vacant grounds, the orchards and fields and gardens began to be built over. Artificers of the meaner kind and trades of an offensive kind were banished to the north part of the town. The lower parts, especially the narrow lanes north of Thames Street, became more and more crowded. Quays under the river wall extended east and west; the foreshore was built upon; the river wall was gradually taken down, but I know not when its destruction began or was permitted. The shipping in the river was doubled and trebled in amount; some of the ships lying off the quays were too large to pass the bridge; the warehouses became more ample; Thames Street, or the street behind the wall, then the only place of meeting for the merchants, was thronged every day with the busy crowd of those who loaded and unloaded, who came to buy and to sell. The ports of the Walbrook and Billingsgate being found insufficient, that of Queen Hithe, then called Edred’s Hithe, was constructed: quays were built round it, and perhaps a new gate was formed in the river wall.

In the year 981, Fabyan says (p. 128) that a fire destroyed a great part of the City of London.

“But ye shall understand that at this day, the City of London had most housing and buylding from Ludgate toward Westmynster, and little or none where the Chiefe or hart of the Citie is at this day, except in divers places where housing be they stood without order, so that many towns and cities, as Canterbury, Yorke, and other, divers in England passed London in building at those days, as I have seen and known by an old book in the Guildhall named Domesday.”

I quote this passage but cannot give credence to the statement, for the simple reason that London was always a place of trade, and that where her shipping and199 her quays and ports lay, there were her people gathered together. Probably at this time the northern parts of the City were not yet built over and occupied. But how could the City successfully hold her own against the Danes if her people lived along Fleet Street and the Strand?

A very important question arises as to the rights of the citizens over the lands lying around the City.

If we consider, for instance, the county of Middlesex, we observe that it is bounded by the river Colne on the west and by the Lea on the east. The Thames is its southern march: that of the north was partly defined by the manors belonging to St. Albans Abbey in after times. The whole of the northern part, however, was covered with a vast forest which extended far on either side of Middlesex, and especially into Essex. Another forest occupied the greater part of Surrey, beginning with wastes and heaths as soon as the land rose out of the marsh.

Some kind of right over these forests, and especially over that in the north, which was especially easy of access, was necessary for the City, as much as its rights over the river. For as the river was full of fish and the marshy river-side was full of innumerable birds, so the forest was full of game—deer, boar, hares, rabbits, and every kind of creature to be hunted and trapped and to serve as food. Also200 the forest furnished timber for building purposes, a feeding-ground for hogs, and wood and charcoal for fuel. The City would not exist without rights over the forest.

If we ask what these rights were, we find that London certainly claimed possession of some lands. Thus in the A.S. Chronicle it is stated that in the year 912 “King Edward took possession of London and of Oxford, and all the lands which owed obedience thereto.” What were these lands? Surely they lay outside the wall.

In the laws of Athelstan, injunctions are laid down for the pursuit of thieves “beyond the March.” What was the March?

In the laws of Cnut the right of every man to hunt over his own land is recognised.

And in Henry the First’s Charter we find the clause, “And the citizens of London shall have their chaces to hunt, as well and fully as their ancestors have had: that is to say, in Chiltre, and in Middlesex, and in Surrey” (see p. 279).

In the same Charter, which was avowedly a recognition of old rights, he gives them the county of Middlesex, with which was included the City of London, “to farm” for the annual payment of £300 a year.

From all of which it appears that the county of Middlesex had been regarded as including London, and, in a sense, a part of London, and that a large part of its lands “owed obedience” to London. In that part the citizens could hunt, just as they could fish in the river and trap birds in the river-side marshes.

II. he Trade of the Town

The early trade of London can be approximately arrived at by taking into consideration (1) that London was the principal receiving, distributing, and exporting place; (2) what it had to sell; and (3) what it wanted to buy.

Nearly everything that was wanted was made on the farms and in the towns. On the farms, the butter, cheese, bread, beer, bacon, were prepared; the grain was grown and ground; the fruit and vegetables were grown in the gardens; the honey was taken from the hives; spinning, weaving, carpentering, clothing, shoemaking were all carried on in the house. Nothing that could be made in the house was bought; nothing that could be made in the house was exposed for sale in the market. What, then, did the people want, and what did they buy? First, they wanted, as necessities, metal for working, weapons, knives, and utensils. Next they wanted salt. Iron and salt were the two absolute necessities of life that could be obtained only by purchase or by barter. If we pass on to luxuries, the wealthier class drank foreign wine in addition to home-made beer, cider, and metheglin; they dressed in foreign silk; they used gold and silver cups, which were made by London goldsmiths; they201 imported foreign glass; spices brought from outre-mer; and weapons made abroad of finer temper and better workmanship than their own. The Church wanted ecclesiastical vestments, pictures, incense, and gold and silver vessels. All these things the City had to offer and to sell. For purposes of purchase or of exchange the City was prepared to buy slaves, wool, metal, corn, and cattle. All over the country the people bred slaves and sold them; they sent to London large quantities of wool; they also sent lead, tin, iron, jet, fish, and cattle. And there was a great demand among the foreign merchants, though there was but a small supply, for the lovely embroidery of the Anglo-Saxon women, and for the beautiful goldwork of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmiths. The position of the goldsmiths in London, where they were the richest and most important citizens, proves that there was more than a home demand for their work. The words used for the arts and for many articles of common use show that they were at first imported, and from a nation where the Latin language was largely used. Common objects, such as candle, pin, wine, oil; names of weights and measures; names of coins are also derived from Roman sources. Wright’s theory that the people in the cities spoke Latin, and that the Saxon gradually became amalgamated with the people in the cities before the grand irruption may account for the survival of Latin names for common objects. One means of introducing these words may have been the communication kept up by the Church with the Continent, and especially between the monasteries of England and France.

202

That the trade of London was large and constantly increasing is certain. The abundance of gold in the country is instanced by the wealth of the shrines and the monasteries, and the importance and value of the exports. Sharon Turner23 sums up this advance in trade in such general terms as I have indicated:—

“The property of the landholders gradually multiplied in permanent articles raised from their animals, quarries, mines, and woods; in their buildings, their furniture, their warlike stores, their leather apparatus, glass, pigments, vessels and costly dresses. An enlarged taste for finery and novelty spread as their comforts multiplied. Foreign wares were valued and sought for; and what Anglo-Saxon toil or labour could produce, to supply the wants or gratify the fancies of foreigners, was taken out to barter. All these things gave so many channels of nutrition to those who had no lands, by presenting them with opportunities for obtaining the equivalents on which their subsistence depended. As the bullion of the country increased, it became, either coined or uncoined, the general and permanent equivalent. As it could be laid up without deterioration, and was always operative when it once became in use, the abundance of society increased, because no one hesitated to exchange his property for it. Until coin became the medium of barter, most would hesitate to part with the productions they had reared, and all classes suffered from the desire of hoarding. Coin or bullion released the commodities that all society wanted, from individual fear, prudence, or covetousness, that would for its own uses have withheld them, and sent them floating through society in ten thousand ever-dividing channels. The Anglo-Saxons were in this happy state. Bullion, as we have remarked, sufficiently abounded in the country, and was in full use in exchange for all things. In every reign after Athelstan the trade and employment of the country increased.”

The principal work of London was that of collecting and distributing. The port was the centre to and from which the whole business of the country came and went. It was the king’s part to maintain the high roads, but the Roman203 skill in road-making was lost; branching off from the highways, in connection with the villages, were tracks through the forests and over the moors. It is an indication of the old spirit of tribal separation that merely to be seen on such a track was suspicious. “... If a far coming man or a stranger journey through a wood out of the highway, and neither shout nor blow his horn, he is to be held a thief and either to be slain or redeemed.” Many of the monasteries lay far outside the high road and in the midst of woods; they were apparently in communication with the world by the medium of streams and rivers. Tintern, Fountains, Dryburgh, Crowland, Ely, for instance, stood beside streams or rivers.

There is abundant evidence as to the extent of the trade carried on in the port of London. There were merchants from Gotland, that strangely-placed emporium of eastern and northern commerce. Thousands of coins have been found on the island—Roman, Byzantine, and Anglo-Saxon, giving evidence of the wealth and enterprise of the merchants, who conducted their caravans across Russia and their ships from the Baltic to the German Ocean and the shores of the Bay of Biscay. We hear of Frisian merchants trading to “Lunden tunes Hythe” in the seventh century. The Norsemen were not all pirates. Othere describes the trade with England in skins of bear, marten, otter, reindeer, in eider-down and204 whalebone; in ropes made of whale and sealskin. In Ethelred’s laws we read of Frisians, called Flandrenses, of the men of the Emperor, men of Rouen, of Normandy, and of France.

It would seem that the greater part of the foreign trade remained in the hands of the foreign merchants, but not all. Athelstan conferred the rank of Thane on one who had voyaged three times to the Mediterranean. And in the Dialogues of Ælfric we have the English merchant’s own account of himself and his trade:—

“I say that I am useful to the king and to ealder men and to the rich and to all people. I ascend my ship with my merchandise and I sail over the sea and sell my things and buy dear things which are not produced in this land, and I bring them to you here with great danger over the sea: and sometimes I suffer shipwreck, with the loss of all these things, scarcely escaping myself. ‘What do you bring to us?’ ‘Skins, silks, costly gems, and gold; curious garments, pigments, wine, oil, ivory and orichalcous; copper and tin, silver, glass, and such like.’”

The voyage of ships from the south and the south-east to London was much safer than we should expect for such small craft as then formed the trading vessels—short, unwieldy, carrying a single mast and a single sail. The ships bound for London hugged the shore round the South Foreland and then, instead of sailing round the North Foreland, they passed into the estuary of the Thames by the shallow arm of the sea called the Wantsum, which there divided Thanet from the mainland and made it an island. At either end of this passage the Romans had constructed a fortress: that on the north called Regulbium, now Reculver; that on the south Rutupiæ;, now Richborough. The latter stood upon a small island separated from the mainland by a narrow channel. The site of Sandwich was another islet lying south of Rutupiæ. The passage was kept open partly by the flow of two or three rivers into it from the highlands of Kent. It gradually, however, silted up and shrank; yet ships continued to pass by this channel until the sixteenth century, when it became too shallow for the lightest ships. The Wantsum must be borne in mind whenever one speaks of early navigation to and from the port of London, because it saved the ships from the rough and dangerous passage round the North Foreland.

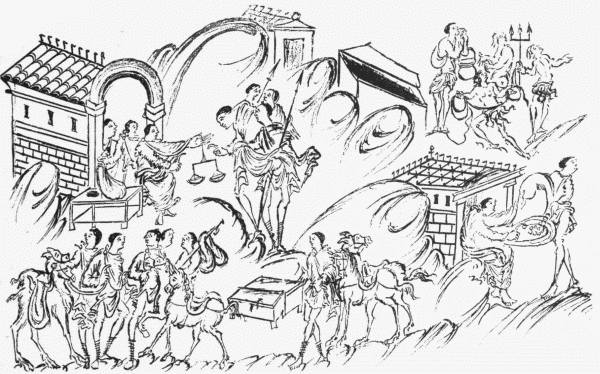

The business of distribution, collection of exports, and internal traffic was conducted entirely by English merchants. Every year the chapman started on his rounds. He set out with his caravan of horses laden with goods and conducted by a troop of servants, all armed for defence against robbers; the roads were cleared of wood and undergrowth on either side to prevent an ambush—they were the old Roman roads, many of which still continue; the antiquarian is pleased to find evidences here and there of a road decayed and not repaired, but deflected by an easier way. Where there were no Roman roads there were tracks and bridle205paths; forests covered the country, and even in summer there was danger of quagmires and bogs. The chapman rode not from village to village, or from house to house, but from one market-place to another, reporting himself to the Reeve on his arrival. When the season was over, when he had sold or exchanged his stock, he returned to London, his caravan now loaded with wool, skins, and metals for export, and perhaps with a company of miserable slaves to be sold across the seas.

The Gilds or Guilds, out of which sprang so great a number of trade corporations and companies, are met with very early. We shall have to consider this subject later on; let us note here, however, that the actual rules of many early Guilds have survived. They were not trades unions: that is, they did not exist for the purpose of keeping up prices and wages. They were essentially social, even convivial in character; they were benefit societies; and they were religious. We have the complete code of the “Frith Guild” of London under Athelstan. The laws are drawn up by the Bishop and the Reeve. The members, who were numerous, met together once a month for social purposes; they feasted and drank together; when a member died each brother gave a loaf, and sang, or paid for singing, fifty psalms. There was an insurance fund to which every member contributed fourpence in order to make good the losses incurred by the members; they also paid a shilling towards thief-catching; they were divided into companies of ten and into groups of hundreds; each company and each group had its own officer. The pursuit and206 the conviction of thieves were the principal objects of this Guild. In a commercial city theft or the destruction of property is the crime which is most held in abhorrence by the citizens.

There was a Guild of another kind, peculiar, apparently, to the City of London. It was called the Cnihten Guild (see p. 329). We shall have occasion to speak of this Guild at greater length farther on. For the present it is enough to say that it was in all probability—for its laws have perished—an association bound together by religious forms and vows for the defence of the City—the “Cnihten” were in fact the officers of the City militia, which consisted of all the able-bodied citizens; they were trustees for the funds collected for the purpose of providing arms for the citizens; they administered an estate belonging to the town called the Portsoken, lying outside Aldgate, whose rents were received and set aside, or expended in the repair of gates and walls, as well as providing arms.

Attempts have been made to derive the Anglo-Saxon Guilds from the Roman collegia. It is not impossible, supposing that the imitation came through Gaul. At the same time, the points of resemblance on which the theory rests are so extremely slight that one is not disposed to accept it as proved. That is to say, they are points of resemblance such as naturally belong to every association of men made for purposes of mutual support and for the maintenance of common interests. Thus:—

1. Under the Roman Empire there existed collegia privata, associations of men bound together for trade purposes.

2. They were established by legal rights.

3. They were divided into bodies of ten and a hundred.

4. They were presided over by a magister and decuriones—a President and a Council.

5. They had their Treasurer and their Sub-Treasurer.

207

6. They could hold property in their corporate capacity.

7. They had their temples at which they sacrificed.

8. They had their meeting-houses.

9. They had a common sheet.

10. They had jus sodalitii, the laws, rights, and duties of the members.

11. They admitted members on oath.

12. They supported their poor.

13. The members had to pay contributions and subscriptions.

14. They buried their dead publicly.

15. Each had its day of celebration or feast.

Now, suppose we found among the Chinese or the ancient Mexicans institutions with similar laws, should we be justified in claiming a Roman origin for them? Not at all. We should merely note the facts, and should acknowledge that humanity being common to every age and every country, such rules must be laid down and maintained by every such association as a Company or Guild in the interests of any trade or mystery. So far and no farther the Anglo-Saxon Guild is a copy of the Roman collegium. Unless further points of resemblance are found, we shall be justified in believing that the Guild was not derived by the Saxon from the Roman, and that the latter was not preserved among the provincial towns of England. Against the theory it may also be argued that if it was so preserved, every Guild208 being separated from every other could develop on independent lines, and that some of the Roman names at least would be preserved, and some of the Roman customs, apart, that is, from the customs common to every such association in every age and in every country.

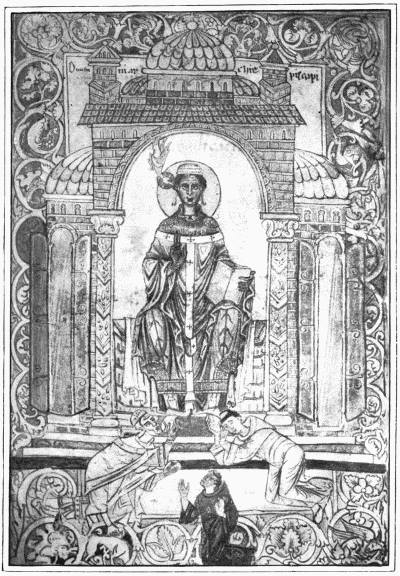

III. he Religious Foundations

The religious spirit, which has always been found among the Teutonic peoples, was strongly manifested in the Saxon as soon as he became converted. He multiplied monasteries and churches; all over the country arose monastic houses; Bede mentions nineteen of them, including those of Ely, Whitby, Iona, Melrose, Lindisfarne, and Beverley. He does not, however, include Westminster, Romsey, Barking, or Crowland. Kings, queens, princesses, and nobles, all went into monasteries and took the vows; partly, no doubt, from fear of losing their souls, but partly, it is certain, from the desire to enjoy the quiet life, free from the never-ending troubles of the world; free also from its temptations and from its attractions. The monastery provided peace in this world and bliss in the world to come. It has been too much the custom to deride the rule and the discipline, the daily services, the iteration that made prayer and praise a mere mechanical routine. Yet it is easy to209 understand the kind of mind on whom this deadening effect would be produced. It is also easy to understand the kind of mind to which a rigid rule would be like a prop and a crutch on life’s pilgrimage; to which daily services, nightly services, perpetual services, would be so many steps by which the soul was climbing upwards. Again, to a harassed king, arrived, after many years of struggle and battle, at middle age or old age, think how such a house, lying in woods remote, among marshes inaccessible, would seem a very haven of rest! Or again, to the princess who had suffered the violent and premature deaths of her brothers, her father, most of her people; who remembered the tears and grief of her widowed mother; who had passed through the bereavements which made life dreadful in a time of perpetual war; how admirable would it seem to preserve her virginity even in marriage, and, as soon as might be, to retire into the safety and the peace of the nunnery!

In the year 731, the year of his death, Bede wrote:210 “Such being the peaceable and calm disposition of the time, many of the Northumbrians, as well of the nobility as of private persons, laying down their weapons, do rather incline to dedicate themselves and their children to the tonsure and monastic vows than to study martial discipline. What will be the end thereof the next age will show.”

The next age did show very remarkably what happens to a country which puts its boys into monasteries. In the next age the people continued still to flock into the monasteries; they not only deserted their duties and their homes, they also deserted their country; they flocked in crowds on pilgrimage to Rome as to a very holy place; noble and ignoble, laity and clergy, men and women, not only went on pilgrimage, but went to Rome in order to die there. Those who could neither take the monastic vows nor die at Rome put on the monastic garb before they died.

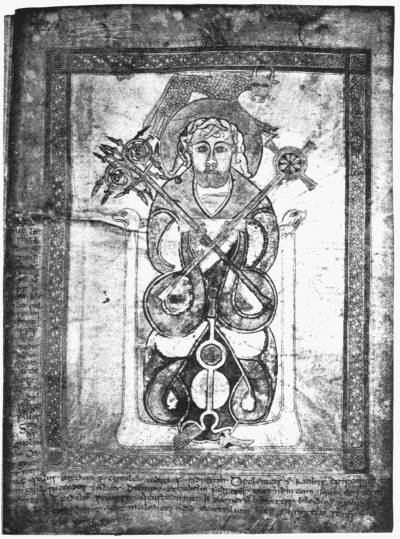

Anglo-Saxon London, during the eighth century, thus became profoundly religious, and although the history of the time is full of violence, it is also full of exhortations to the better life. The Bishops constantly ordered the reading of the Gospels. Every priest, especially, was to study the Holy Book out of which to preach and teach. The modern spirit of an Anglo-Saxon sermon is most remarkable, and this in spite of the superstitions in which the time was plunged. The churches, for instance, were crammed with relics; perhaps the people regarded them as we regard collections in a museum. Here were kept pieces of the sacred manger, of the true Cross, of the burning bush, of St. Peter’s beard, of Mary Magdalene’s finger. There were also the popular beliefs about witchcraft. The priests inveighed against witches—“that the dead should rise through devil-skill or witchcraft is very abominable to our Saviour; they who exercise such crafts are God’s enemies and truly belong to the deceitful Devil.” The priests were also zealous in forbidding and in stamping out all heathen survivals, such as fountain worship, incantations of the dead, omens, magic, man worship, the abominations practised in various sorts of witchcraft, worship of elms and other trees, of stones, and other “phantoms.” Long after Christianity had covered the land, the people practised their old incantations for the cure of disease, for good luck in enterprise, against poisons, disease, and battle. They had a thousand omens and prognostics; days were lucky or unlucky; days were good or bad for this or that kind of business—it is within living men’s recollection that Almanacks were published for ourselves giving the lucky and the unlucky days—those beliefs are hardest to destroy which are superstitious and irrational and absurd. Are we not living still in a mass of superstitious belief? It is sufficient to record that the Saxons were as superstitious as our grandfathers—even as superstitious as ourselves.

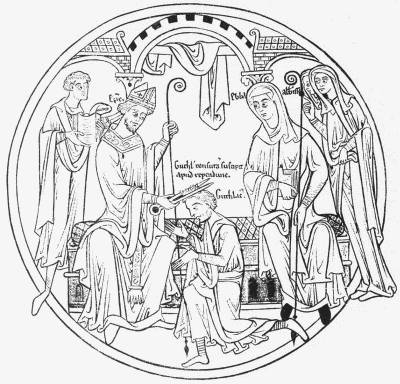

It is interesting to note the simple and beautiful piety of Bede and other Anglo-Saxon writers, and to mark the extraordinary credulity with which they relate marvels and miracles. Every doctrine had to be made intelligible, and explained and enforced by a special miracle. Take, for instance, the doctrine of the efficacy of masses for the dead. Who could continue in doubt upon the subject after such testimony as the following? Who can argue against a miracle?

In the year 679—only a few years before the history was written—a battle was fought near the river Trent between Egfrith, King of the Northumbrians,211 and Ethelred, King of the Mercians. There was left for dead on the field of battle one Imma, a youth belonging to the king. This young man presently recovered, and binding up his wound tried to escape unseen from the field. Being captured, however, he was taken to one of Ethelred’s earls. Being afraid of owning himself for what he was, he said he was a peasant who had brought provisions for the army. The earl ordered him to be cared for and properly entertained as a prisoner. Now he had a brother called Tunna, a priest, and the Abbot of a monastery. This priest heard that Imma was dead, and went to search for his body on the field of battle. He presently found one so like that of his brother that, carrying it to the monastery, he buried it and said masses for the soul. Now when Imma had recovered of his wounds, the earl ordered him to be bound so that he should not escape. Lo! as fast as the bonds were laid upon him they were loosened. The earl suspected witchcraft; he was assured by Imma that he knew no spells. Being pressed, however, he confessed who and what he was, viz. no peasant, but a soldier belonging to King Egfrith. Then the earl carried him to London and there sold him as a slave to a certain Frisian, who bound him with new fetters. But at the third hour of the morning they all fell off; and so every morning; wherefore the Frisian, not knowing what to do with this miraculous slave, allowed him to return on promise of sending his ransom. Now when Imma conversed with his brother, he discovered that the loosening of his bonds had been miraculously effected in answer to the masses said for his soul.

The ravages of the Danes in the eighth and ninth centuries destroyed most of the monasteries. For, at first, being heathens, they rejoiced in the destruction and pillage of holy houses and churches, which were rich, full of precious things in gold and silver, embroidery, pearls and gems, silks and fine stuffs. Wearmouth, they destroyed, also Jarrow, Tynemouth, Coldingham, Crowland, Peterborough. When212 the destroyers retired, those of the monks who had escaped murder timidly came back. Crowland Abbey, for instance, found itself reduced to the Abbot and two monks.

When Alfred had restored peace, he tried to renew some of the monasteries, but failed; no one would become a monk. With nunneries he succeeded better, founding one at Shaftesbury and one at Winchester. Glastonbury, in the time of Dunstan, was served by Irish priests. In the precinct of Paul’s Minster there was a college—St. Martin’s-le-Grand was a college; but there was in London at this time neither monastery nor nunnery. Why?

It may be explained on the ground that at the time when the great zeal for monasteries moved the hearts of the people there was comparative peace in the land, and it was sought to build a religious house far away from what were thought to be the disturbing influences of a town. For instance, St. Erkenwald, Bishop of London, founded two houses, but placed neither in London; one of these he built at Barking down the river, the other at Chertsey up the river. Other instances occur. Romsey, Crowland, Medehamsted (Peterborough), Lindisfarne, Iona, Ely, Glastonbury, not to speak of many later foundations, were placed in quiet retreats far from the busy world. Westminster, it is true, was built on an island once populous and lying on the highway of trade; but the earlier foundation was destroyed by the Danes, and Edward’s House arose long after the highway had been turned aside and most of the trade diverted. Still, Westminster was never remote from the haunts of men, and it may be observed that when the foundation of new houses began they were erected in and around London itself, with no thought of seclusion. Again, when the Danish troubles came upon the land and the monasteries were sacked, for many years the monastic life became impossible; the old desire for it entirely vanished, and long years passed before it awakened again. When it did, monastic houses were founded within the walls of London, or close beneath the protection of the walls, as at St. Mary Overies and Bermondsey and Aldgate. The Danish pillage was not forgotten.

Another explanation of the absence of monastic houses in Saxon London may be the fact, which one is apt to overlook, that every Minster was provided with a college, or a monastic house where the priests—not monks—lived the common life, though not yet the celibate life; where they had a school and where they brought up boys for the Church. In Domesday Book there are no lands owned by religious houses in London except by the Church of St. Paul’s, which had lands in Essex and elsewhere; by certain individual canons, the Bishop of London, who had lands in Middlesex, Hertford, and Essex; and by the Church of St. Martin’s, the Abbey of Westminster, and the Abbey of Barking.213

The churches of London, with the houses, were at first built of wood. You may see a Saxon church, such as those which were dotted all over the City area, still standing at Greenstead, near Chipping Ongar, in Essex (see p. 211). When the houses began to be built of stone, the churches followed suit; you may see a stone Saxon church at Bradford-on-Avon, near Bath. The churches were quite small at first, and continued to be small for many centuries. They were by degrees provided with glass, with richly decorated altars, with chapels and with organs: in the last respect being better off than their successors in the eighteenth century, when many City churches had no organ. Bede describes an organ as a214 “kind of tower made with various pipes, from which, by the blowing of bellows, a most copious sound is issued; and that a becoming modulation may accompany this, it is furnished with certain wooden tongues from the interior part, which the master’s fingers skilfully repressing, produce a grand and almost a sweet melody.”

And Dunstan, who was a great artificer in metals as well as a great painter, constructed for himself an organ of brass pipes.

It is interesting to gather, from the dedications of the City churches, those which certainly date from Saxon times. Thus there are five dedicated to Allhallows, of which four are certainly ancient; of the churches dedicated to Apostles, there are two of St. Andrew, three of St. Bartholomew, one of St. James, one of St. Paul, three of St. Peter, one of St. Stephen, four of St. Mary, one of Mary Magdalene; of later saints, St. Martin, St. Bridget, St. Benedict, St. Anne, St. Clement, St. Giles are represented, while Saxon or Danish saints are found in St. Ethelburga, St. Swithin, St. Botolph, St. Olave, St. Magnus, St. Vedast, and St. Dunstan. None of the Norman saints seem to have crossed the water. None, certainly, supplanted the Saxon saints, while not one British saint remained in Saxon England, which shows how different was the Norman Conquest from the Saxon occupation.

If ecclesiastical law means anything, then the London citizen must have spent most of his time in doing penance. Besides the common crimes of violence, perjury, theft, and so forth, the Church advanced the doctrine that there were eight capital crimes, namely, pride, vainglory, envy, anger, despondency, avarice, greed, and luxury. For greed a man had to fast and do penance for three years. For despondency, he had to fast on bread and water till he became once more exhilarated.

The chief weapon of the Church at a time when the executive is weak is penance. For the Anglo-Saxon his priest was armed with a code of penances so long and so heavy that one cannot believe that it was ever enforced. Can we, for instance, believe that free men would consent to live on the coarsest food and do penance for three years as a punishment for eating with too great enjoyment? We are told that if a man killed any one in public battle he was to fast forty nights. Then King Alfred must have been doing penance all the days of his life—which is absurd. Again, can one believe that sinners consented to wear iron chains round the body, to lie naked at the feet of the person offended, to go about with a rope round their necks, to abstain from water, hot or cold? Can we believe that any one, especially any rich or noble person, would sell his estate, give one-third to the poor, one-third to the clergy, and keep no more than one-third for himself and his family?

Penance, however, could be commuted by payments in money. This shows, not the greed and avarice of the Church, but the weakness of the Church. Another way of getting through penance was by paying people to perform the penance for the sinner. Thus, a man who was ordered a thirty-six days’ fast could engage twelve men to fast for three days each. Or if he was ordered a year’s fast, he would arrange for 120 men to fast, in the same way, for three days each. As I said above, it is the weakness of the Church that one perceives. The Bishops denounced215 crime; they showed the people how grievous a sin was this or that, by imposing heavy penance; then because only a few would consent to perform such penances, they were obliged to be content with evasions and vicarious performance. As the Church grew stronger, penance became more reasonable.

There was a church in nearly every street, and a parish to every church. Some of the churches were built as an act of penance. We are sometimes tempted to believe that the power of the Church must have been an intolerable tyranny; yet the violence of the time called for the exercise of arbitrary authority, and, at the very worst, it was better to be in the hands of the Church than in those of the King.

IV. he Temporal Government

In the administration of the City, the Bishop and the Portreeve were the two principal officers; the former represented more than the ecclesiastical life, because the Church governed the life of every man at every step in his pilgrimage from the cradle to the grave. The Portreeve was the king’s officer: he looked after customs, dues, tolls, etc. The port is neither “Porta,” the gate; nor “Portus,” the harbour; it is “Portus,” the enclosed space: “Portus est conclusus locus quo importantur merces et inde exportantur” (Thorpe, 1. 158). The Portreeve was the civil magistrate, as the Bishop was the ecclesiastical. Other officers were the “Tungerefa,” or Tunreeve, whose business it was to inquire into the payment of custom dues. The “Caccepol” (Catchpole), or Beadle, was perhaps a collector. And there were the Jurats or Jurors, called sometimes testes credibiles, who acted as witnesses in every case of bargain or sale. The laws of Edgar said: “Let every one of them on his first election as a witness take an oath that neither for profit, nor for fear, nor for favour, will he ever deny that which he did witness, nor affirm aught but what he did see and hear. And let there be two or three such sworn men as witnesses to every bargain.” The “Wic-reeve” is also mentioned, but this is probably only another name for Town-reeve. He is mentioned in an edict issued by two Kentish kings, Hlothhere and Edric (673-685). “If any Kentish man buy a chattel in Lundewic, let him have two or three witnesses or a king’s wic-reeve.” Wright takes this officer to have been one appointed by the Kings of Kent to look after their interests in a town belonging to the Kings of Essex. Why should it not mean simply the reeve of the port, i.e. the reeve of the Kings of Essex? “If it be afterwards claimed of the man in Kent, let him then vouch the man who sold it him, or the wic at the king’s hall.” Criminals were tried in open court by their fellows. They might be acquitted by the oaths of those who had known them long. If they were found guilty, the punishments were cruel: they were deprived of hands, feet, tongue, eyes; women were hurled from cliffs into the river, or burned; floggings were inflicted. Ordeals were practised—that of the “corsned,” or consecrated barley-bread, which only the216 innocent could swallow;—this ordeal was supposed to have killed Earl Godwin; that of cold water, that of hot water, that of hot iron. Not, however, the ordeal by battle. Of all other ordeals the event was uncertain: in that by battle one or the other had to die. The citizen of the tenth century had the greatest possible objection to such an ordeal. Later on, under Norman rule, he protested continually against this liability, until the King conceded his freedom from it.

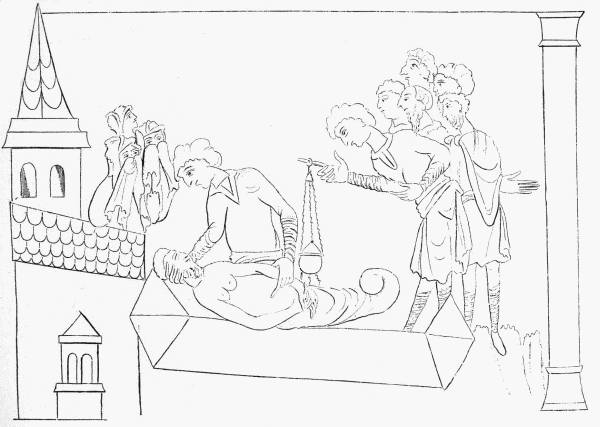

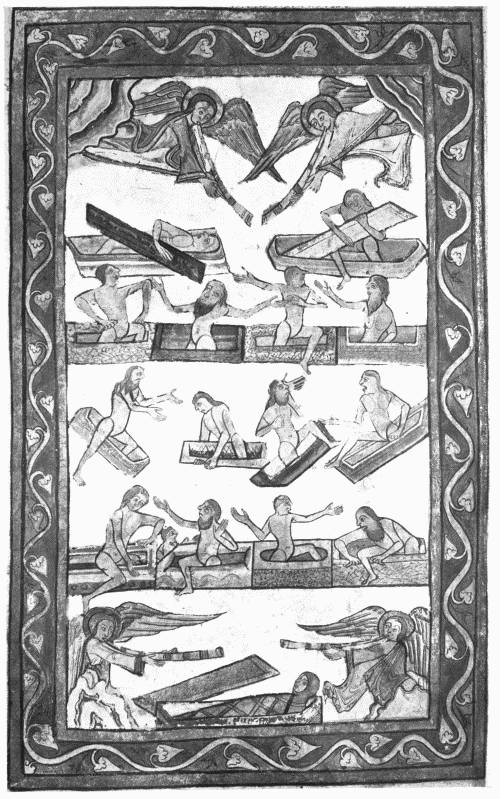

The Anglo-Saxon laws are simply amazing as regards the punishments ordered for those offenders who were of servile rank. Their savage cruelty shows that the masters were afraid of the slaves. If a slave woman stole anything she might be whipped unmercifully, thrown into prison, and kept there; thrown over a precipice, drowned, or even burned to death. In the last case she was to be burned by eighty other women slaves, every one of whom was to contribute a log towards the fire. If a man slave committed a similar offence he might be stoned to death by eighty other slaves, and if one of those eighty missed his mark three times he was to be flogged. Since, however, slaves cost money, and were valuable property, it is not probable that they were often destroyed for slight offences. On the other hand, they were cruelly flogged. A small drawing in a contemporary MS. shows the flogging of a slave. He is stripped naked; his left foot is confined by a circle; two men are flogging him with thorny handles. The cruelty of the punishment, thus brought home to one, seems atrocious. But flogging was not the worst or the most cruel punishment. Every kind of mutilation was practised in ways almost unspeakable. Mutilation, indeed, was continued as a punishment long after the Conquest. We217 shall see, for instance how Henry I. punished the “moneyers” who had debased the coin by striking off their right hands and depriving them of their manhood. Eyelids were cut off, noses, lips, ears, hands, feet; the victims of this barbarity were to be seen on every road in every town. Those who were not slaves, but freemen, were, as a rule, treated with far more clemency. First, for the man not taken red-handed, there was the ordeal to which he might appeal. There was next the “compurgation,” in which the accused had to find a sufficient number of reputable persons to swear that he was not capable of the offence charged. Or again, many offences could be cleared by penance, and since penance included fasting, which is impossible for the weak and the old, the repetition of prayers and singing of Psalms was allowed as a substitute; and since these do no good except to the penitent, compulsory almsgiving was further allowed as a substitute. So that, although the Church attempted to make of the last mode of punishment a real and substantial fine in proportion to the means of the sinner, the natural, certain, and inevitable result followed: that all crimes could be atoned for by those who could pay the fines, and that in the Christian Church there was one law for the rich and another for the poor. Also, as naturally followed in course of time, it became customary to classify most crimes by a kind of tariff. Those of violence, greed, and lust, which were common in an age of violence, were priced at so much apiece. Those, however, of murder of kin, arson, treason, witchcraft, were held “bootless,” i.e. not to be atoned for by any fine. Then a very curious institution existed, called the Frank pledge. Every man in the country belonged to a tithing or company of ten; every company of ten belonged to a company of a hundred; every crime had to be paid for by the tithing, or the hundred; thus it happened in this way it was made the interest of every one that the tithing or the hundred should be kept free from crime.

The punishment of women by drowning was practised in very early times by the ancient Germans and Anglo-Saxons. It was continued down to the middle of the fifteenth century, when it was finally, but not formally, abolished. But women were drowned on the Continent in the eighteenth century. The London places of execution were the Thames, and the pools of St. Giles, Smithfield, St. Thomas Watering, and Tyburn. Sometimes the criminal was sewn up in a sack with a snake, a dog, an ape—if one could be procured—and a cock.

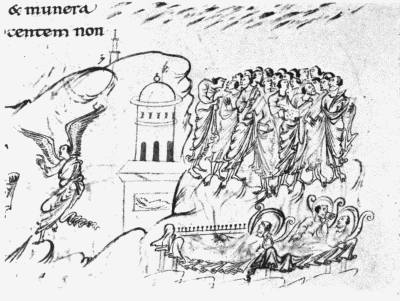

The right of taking a part in the government of his country was always held and claimed by the Anglo-Saxon freeman. Thus in London, all causes were tried, and all regulations for the ordering of the City were made, by the citizens themselves in open court. The Hustings, a Danish Court, was held once a week, on Monday. The Folkmote was held on occasion, and not at stated times. The men were called together by the bell of St. Paul’s, to Paul’s Cross; there, in a tumultuous assemblage, everything was discussed, not without blows and even slaying or wounding, for every man carried his knife. It was difficult to persuade the citizens to meet without arms,218 because to carry no arms was the outward mark of the slave; even the clergy carried arms. Only while performing penance the freeman must lay aside his sword; and that, no doubt, was a greater penalty than the fast. Another distinguishing mark of the freeman was his long hair: the slaves had their hair cut close; the most shameful punishment that could be inflicted on a free woman was to cut off her hair.

Wright is of opinion that the existence of London was continuous, and that it was never taken or sacked by the Saxons. We have seen the evidence for the desertion of the City. He adduces the example of Exeter, where English and Welsh continued to live on equal terms; he acknowledges that this could only have been done by virtue of an original composition with the English conquerors.

He points out, however, apart from his theory, the very important fact that London was in many respects a free commercial city, making laws for itself and claiming privileges and concessions which imply claims to the exercise of independent jurisdiction, notably in the law made by the Bishop and Reeves of London for the citizens in the year 900. Such powers the City certainly possessed and used at that and earlier times; they were, however, powers not laid down by law, but assumed as the occasion demanded, and neither disputed nor allowed by the King. Later on, the citizens pretended to have possessed their privileges from the first foundation of their City, which they carried back as far as the foundation of Rome.

219

V. he Manners and Customs of the People

As regards the poor of London, the laws relating to them were most strict and clear. Everybody had to give to the Church the tenth part of his possessions and incomings: the tithe, according to a law of Ethelred, was to be divided into three equal parts, of which one was to go to the maintenance of the church fabric—the altars, the service of the church, and the offices belonging thereto; the second part was to go to the priests; and the third part to “God’s poor and needy.” Archbishop Egbert issued a canon to the same effect. King Edgar enjoined the same division. And not only did tithes carry with them this provision for the poor, but the faithful were also exhorted to other almsgiving. For instance, if a man fasts, let him give to the poor what he has saved by his abstinence; and if by reason of any infirmity he is unable to fast, let him give to the poor instead. Every church, every monastery, had its guest-house or poor-house, where the poor were received and fed. Archbishop220 Wilfred, in 832, fed daily, on his different manors, twenty-six poor men: to each he gave yearly twenty-six pence for clothing; and on his anniversary he gave twelve poor men each a loaf of bread and a cheese, and one penny. This practice was continued after his death by endowments. In the same way there were endowments for the poor at Canterbury, Ely, and elsewhere. We must, therefore, remember that round every parish church in the City of London there were gathered daily, for their share of the tenth part, “God’s poor and needy”—the aged, the infirm, the afflicted—belonging to that parish.

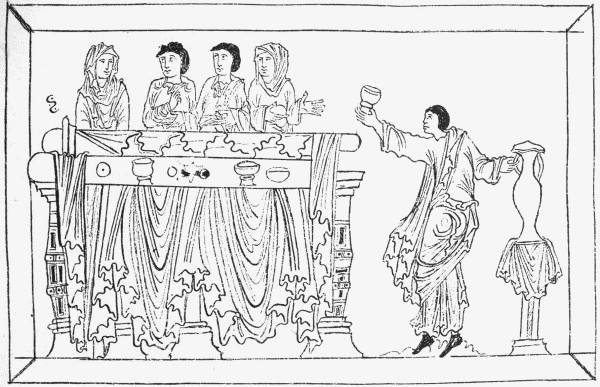

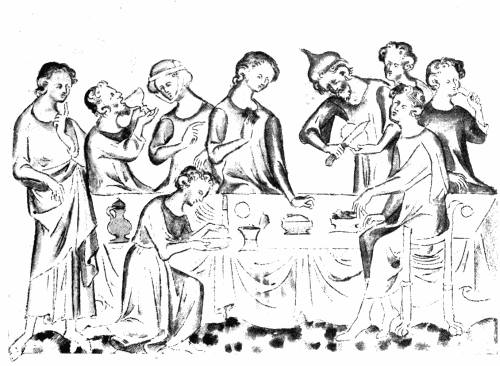

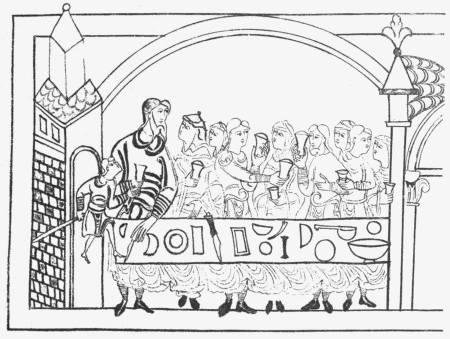

The daily life of the King in his palace or on his journeys is not difficult to make out. That of the people, the priest, the merchant, the craftsman, is impossible to discover—only a few general customs can be noted. To begin with, the Anglo-Saxon was a mighty drinker: in drinking he was only surpassed by the Dane; bishops were even accused of going drunk to church; all classes drank to excess. They had drinking bouts which lasted for days: during this orgy they illustrated their Christian profession by praising the saints and singing hymns between their cups, instead of singing the old war songs; the young king, Harthacnut, as we know, drank himself to death. But the feasting and the hard drinking seldom fell to the lot of the ordinary craftsman.221 We may believe that this honest man drank as much as he could get and as often as he could afford, but ale and mead then, as now, cost money. How the craftsman worked, for what wage, for how long, how he was housed, how he was fed, we may ask in vain.

Like the Dane, the Anglo-Saxon was of an imaginative nature; he not only believed in spirits and demons, but he made a great and complete scheme of mythology into which we need not here inquire; when he was converted to Christianity he surrendered himself to a blind belief in the doctrines of the Church. Many noble and royal persons in the revival of the eighth century showed, as we have seen, the sincerity of their belief so far as to lay down their rank and enter monasteries, or to go off barefooted on pilgrimage. With the majority, their new religion was something added to the old. We are not to222 suppose that this old mythology was known to the common people, any more than the book of Ovid’sMetamorphoses was known to the average Roman citizen. The Christian Church introduced its teaching gradually, being content to pass over many pagan practices. The Church said nothing while the people continued to believe that the foul fiend entered into the body of a person newly dead and walked about in that body all night. They believed in the power of raising spirits, in magic and witchcraft; they wore amulets and charms for protection; they believed in “stacung,” i.e. “sticking,” a method of killing an enemy by which the slayer simply stuck a thorn or a pin into his enemy and prayed that the part wounded might mortify and so cause death. It was an easy method, but one that offered the obvious objection that you cannot stick a pin into any part of a man without causing him pain; nor can you pray at the same time without his hearing the prayer. Therefore one must believe that the would-be murderer ran great risk himself of being murdered. There were, however, instances in which persons were believed to have caused death by this method. In the tenth century, for instance, we get a glimpse of wild justice. We see a man running madly through the streets; he reaches the nearest gate; he flies across the moor, where none pursue him; he is heard of no more. The crowd which ran after him turned back. They made for a house—not a hovel—a substantial house, where he had lived with his aged mother; they beat down the door; they rushed in; they came out shouting that they had found the accursed thing; they dragged out the old woman shrieking for mercy. “Witch! sorceress! She has bewitched Ælsie by sticking and by prayer. He is sick unto death. She must die.” They hauled her along the streets; they reached the bridge; they hurled the poor creature, now covered with blood and shrieking no longer, into the river. She floated for a second; she sank; again she rose to the surface; then she was seen no more, and the crowd returned. The King for his part confiscated the lands of the sorceress and her son.

Loftie gives the following passage concerning this event. It is from a document in the Society of Antiquaries. Note by the way that it proves the existence of the bridge in 960 or thereabouts:—

223

“Here is made known in this writing, that bishop Æthelwold and Wulfstan Uccea exchanged lands, with the witness of King Ædgar and his ‘witan.’ The bishop gave to Wulfstan the land at Washington, and Wulfstan gave him the land at Jaceslea and at Aylesworth. Then the bishop gave the land at Jaceslea to Thorney, and that at Aylesworth to Peterborough; and a widow and her son had previously forfeited the land at Aylesworth, because they had driven an iron pin into Ælsie, Wulfstan’s father, and that was detected: and they drew the deadly thing forth from her chamber. They then took the woman and drowned her at London Bridge; and her son escaped, and became outlaw; and the land went into the hands of the king; and the king then gave it to Ælsie, and Wulfstan Uccea his son gave it again to Bishop Æthelwold, as it is here above said.”

The method of “sticking” was continued, but with modifications. The operator no longer stuck a thorn into his enemy. He made a waxen image of him and stuck pins into the image, with a prayer that the man might feel the agony of the wound; he placed it before the fire, and prayed that as the waxen image melted away, so his enemy might waste away and die. The superstition lingered long; perhaps it still has followers and believers. In the fifteenth century the greatest lady in the land was compelled to do penance and was committed to a life-long prison for practising this superstitious rite.

Philtres and love potions were greatly in request; the people practised astrology and divination. Their medicine was much mixed with superstition: thus they knew the medicinal properties of certain plants, but in using them certain prayers had to be said or sung; they practised bleeding, but not when the moon was crescent and the tide was rising; the use of relics was prescribed for every possible disease.

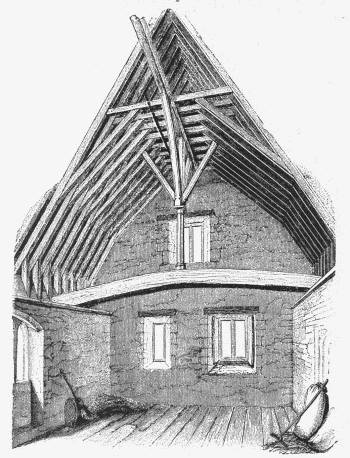

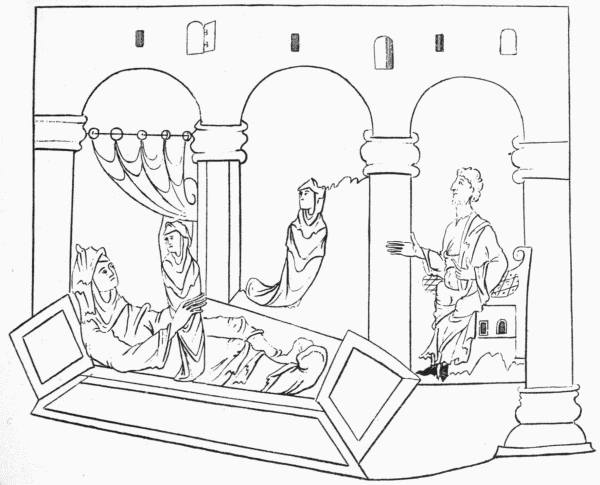

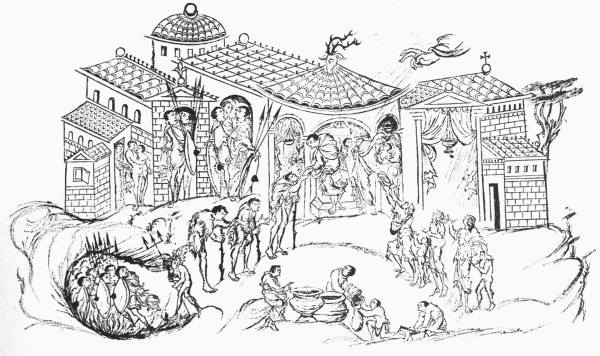

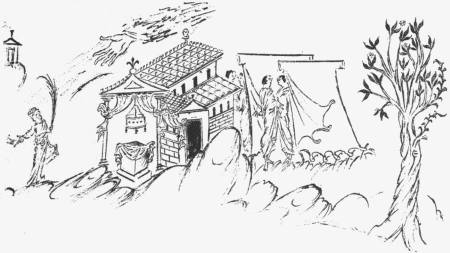

It is a great pity that we have neither an Anglo-Saxon house nor any detailed description of one left. There are, it is true, some drawings of houses in the MSS. of the period, but the buildings are presented conventionally; they are indicated for those who would recognise them without too great an adherence to truth. Take that on p. 225. There is, it will be perceived, a central hall. On one side is the224 chapel—part of the wall is taken out so as to show the lamp burning before the altar; beside the chapel is a small room, perhaps the chaplain’s chamber; on the other side are two chambers: one belongs to the men-at-arms, the other to the maids; the court is full of beggars, to whom the lord and the lady are serving food, while the maids are bringing out clothes for two adults who are standing at the door in a state of Nature. There is a round building at the back—the walls of the house are of masonry up to a certain height, when timber begins; there is but one floor. The hall was hung with cloths or tapestry; it was furnished with benches and with movable tables on trestles.

In the Saxon household the special occupation of the women was the construction of clothing. They carded the wool; they beat the flax; they sat at the spinning-wheel or at the weaver’s loom; they made the clothes; they washed the clothes; they embroidered and adorned the clothes; the female side in a genealogy was called the spindle side. Kings’ daughters, notably the grand-daughters of King Alfred, distinguished themselves by their work with the spinning-wheel and the needle. The Norman admired the wonderful work of the Saxon ladies; the finest embroideries shown in France were known as English work. Thomas Wright (Womankind in Western Europe, p. 60) gives very complete testimony on this point:—

225

“The Anglo-Saxon ladies of rank were especially skilful in embroidery, and that from a very early period. English girls are spoken of in the life of St. Augustine as employed in skilfully ornamenting the ensigns of the priesthood and of royalty with gold, and pearls, and precious stones. St. Etheldreda, the first Abbess of Ely, a lady of royal rank, presented to St. Cuthbert a stole and maniple which she had thus embroidered with gold and gems with her own hands. At a later period, Algiva or Emma, the queen of King Cnut, worked with her own hands a stuff bordered in its whole extent with goldwork, and ornamented in places with gold and precious stones arranged in pictures, executed with such skill and richness that its equal might be sought through all England in vain. Dunstan is said to have designed patterns for the ladies in this artistic work. The early historian of Ely tells a story of an Anglo-Saxon lady who, having retired to lead a religious life in that monastic establishment, the nuns assigned to her a place near the Abbey, where she might occupy herself more privately with young damsels in embroidery and weaving, in which they excelled. We trace in early records the mention of women who appear to have exercised these arts as a profession. We find, for instance, in the Domesday Book, a damsel named Alwid holding lands at Ashley in Buckinghamshire, which had been given to her by Earl Godwin for teaching his daughter orfrey or embroidery in gold, and a woman named Leviet or Leviede is mentioned in Dorsetshire as employed in making orfrey for the king and queen.”

It is also remarked by Wright that the names given to women indicate a high respect for womanhood: such as the names of Eadburga—the citadel of happiness; Ethelburga—the citadel of nobility; Edith (Eadgythe)—the gift of happiness; Elfgiva-the gift of the fairies; Elfthrida—the strength of the fairies, or the spiritual strength; Godiva (Godgifa)—the gift of God.

There are, so far as I know, no traditions of any nunnery in London before the Conquest. The name Mincing Lane, which is certainly Mincheon Lane or Nuns’ Lane, points probably to property belonging to a nunnery. Perhaps there was a nunnery within the City before the occupation by the Danes. If so, it perished and was forgotten. Just as men were required to fight and not to lead monastic lives, so women were required to become mothers of fighting men, and not to enter a cloister. I think there may have been a nunnery, because London did not escape the wave of religious revival, and also because one was necessary for the education of girls. At nunnery schools the girls were educated with far greater care than our own girls till the last twenty years or so. They learned Latin, rhetoric, logic, and, according to Wright, “what we call popular science.” They also learned embroidery.226 “From the statements of the Anglo-Saxon writers, we are led to believe that the Anglo-Saxon nuns had no objection to finery themselves, and they are accused of wearing white and violet chemises, tunics, and veils of delicate tissue, richly embroidered with silver and gold, and scarlet shoes.” (Wright, p. 86.)

The evening of the ordinary man was not wholly given up to drinking. The musicians came in and played on harp and trumpet, pipes, horn, and fiddle. The gleemen sang and recited; the tumbling-girls played their tricks.

The Anglo-Saxon love of music and poetry gives us a higher opinion of the people than we might form from all that we have learned. Applying all his qualities, good or bad, to the Londoner, it will be found that he has transmitted them to the generations coming after him. For he was a lover of freedom, valiant in the field; a lover of order and justice; impatient under ecclesiastical control, yet full of religion; fond of music, poetry, singing and playing; given to feasting and227 addicted to drunkenness. These attributes distinguished the Londoner in the tenth century, and they are with him still after a thousand years.

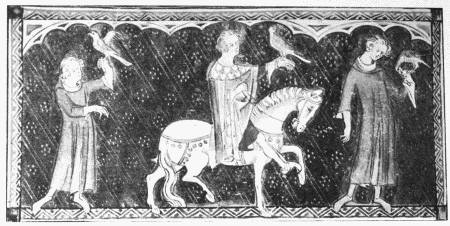

The sports and pastimes of the City were the same for London as for the rest of the country. The citizens were passionately fond of hunting and hawking; they baited animals, as the bull, the bear, and the badger; they were fond of swimming, skating, and rowing, of dancing, and of tomfoolery, jumping, tumbling, and playing practical jokes. Of these amusements, hunting was by far the most popular with all classes. We have seen that the Londoner had deep forests on all sides of him, beyond the moor on the north of his wall, beyond the Dover causeway on the south, beyond the Lea on the east, beyond Watling Street on the west. The forests were full of wild cattle, bears, elk, buffalo, wild boars, stags, wolves, foxes, hares, and the lesser creatures; as for the wolves, they were a terror to every village. Athelstan and Edgar organised immense hunts for the destruction of the wolves; under the latter they were so greatly reduced in number that he is generally said to have exterminated them. As regards the hunting of the elk or the wild boar, it was a point of honour to meet the creature face to face after it had been roused from its lair by the dogs, and driven out maddened to turn upon its assailant. In single combat the hunter met him spear and knife in hand, and either killed or was killed. Sometimes nets were employed; these were stretched from tree to tree. Dogs drew the creatures into the nets, where they were slaughtered. Once Edward the Confessor, a mighty hunter, discovered that his nets had been laid upon the228 ground by a countryman. “By God and His Mother!” cried the gentle saint, “I will serve you just such a turn if ever it comes in my way.”

The country was famous for its breed of dogs. There were bloodhounds strong enough to pull down bulls; wolfhounds which could overtake a stag or a wolf or a bear; a kind of bulldogs remarkable for their overhanging jowls; harriers, greyhounds, water spaniels, sheep-dogs, watch-dogs, and many other kinds.

The Game Laws, which restricted the right of hunting, formerly universal, were introduced by Cnut. Every man, however, was permitted to hunt over his own land.

Akin to hunting was the sport of hawking. This was greatly followed by ladies, for whom other kinds of hunting were too rough. Hawks of good breed were extremely valuable. It was not only by hawking that birds were caught. The Londoner employed nets, traps, slings, and bird-lime. He had only to go down the river as far as Barking or Greenwich to find innumerable swarms of birds to be trapped and netted. Of his indoor pastimes one must not omit to mention the making and answering of riddles, a game with pawns—“taeflmen”—and dice, called “taefl,” and the game of chess. The last of these was a fearful joy on account of the rage which seems always to have seized the man who was defeated. Witness the following anecdote:—

“Among the most enthusiastic of chess-players was Cnut the Great, but he was by no means an agreeable antagonist. When he lost a game, or saw that he was on the eve of doing so, he very commonly took up the huge chess-board on which he played, and broke it on the head of his opponent. He was on one occasion playing with his brother-in-law, the Earl Ulf, when the earl, seeing that he had a forced mate, and knowing the king’s weakness for knocking out the brains of successful antagonists, quietly left the table. Cnut, who guessed his motive, shouted after him: ‘Do you run away, you coward?’ To which the other, who had lately rescued the king in an unfortunate engagement with the Swedes, replied, ‘You would have been glad to have run faster at the Helga, when I saved you from the Swedes who were cudgelling you.’ Cnut endeavoured to bear the retort patiently, but it was too irritating for his temper. On the following morning he commanded one of his Thanes to go and murder Ulf; and though, in anticipation of the king’s vengeance, Ulf had taken sanctuary in the church of St. Lucius, the bloodthirsty order was carried into effect.”

The education of the boy was conducted at monasteries. One knows that there were schools in every monastery, and that every minster had its school; and that probably the four oldest schools of London—St. Paul’s, St. Martin’s, St. Anthony’s, and St. Mary-le-Bow, were of Anglo-Saxon foundation. We know, further, that at these schools the teaching was carried on by means of catechism, and that the discipline was severe, but we do not know what children were admitted to these schools, and whether the child of the craftsman was received229 as well as the child of the Thane. Athletics were not neglected—leaping, running, wrestling, and every kind of sport which would make the body more active and the frame more capable of endurance were encouraged. Until the time of Alfred very few even of the highest rank could read or write. The monasteries with their schools did a great deal to remove the reproach. The boys rose before daybreak and joined the brethren in singing the Psalms appointed for the early service. They assisted at first mass and at the mass for the day; they dined at noon and slept after dinner; t hey then repaired to their teacher for instruction.

Food in London was always plentiful; it was very largely the same as at present. The people killed and ate oxen, sheep, and swine; they had game of all kinds; wild birds in myriads frequented the marshes and the lowlands of Essex; the rivers were full of fish. Barley-bread was eaten by children and the lower orders; they had excellent orchard-land, and a plentiful supply of apples, pears, nuts, grapes, mulberries, and figs. In the winter they had salted meat. Their drink was ale, wine, mead, pigment, and morat. Pigment was a liquor made of honey, wine, and spice. Morat was a drink made of honey mixed with the juice of mulberries.

The Londoner’s house was luxurious, according to the luxury of the time. The walls were adorned with hangings, mostly of silk embroidered with figures in needlework. These hangings and curtains were of gaudy colours, like the fashionable dresses. The benches, seats, and footstools were richly carved. The tables were sometimes decorated with silver and gold. The candlesticks were of bone or of silver. The mirrors were of silver. The beds were provided with rich and soft pillows and coverings, bearskins and goatskins being used for blankets. There was great store of silver cups and basins; the poorer sort used vessels of wood and horn. Glass began to come into general use about the time of the Norman230 Conquest. At least twelve different precious stones were known. Spices were also known, but they were difficult to procure and highly prized. The warm bath was used constantly, but not the cold bath, except as a penance.

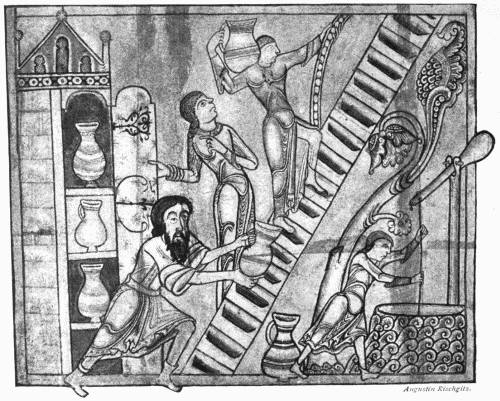

In every city, town, nay, every monastery and every village, it was necessary that there should be artificers to make everything that was wanted. The women did the weaving, sewing, dressmaking and embroidery. We need not attempt to enumerate the trades of the men. A list of them will be found in Mediæval London. (See vol. i. App. ii.)

The population of London can only be guessed, but there are certain facts which afford some kind of clue. Thus, when Alfred entered the City there was practically no population, unless the slaves of the Danes remained. The City filled up rapidly with the increase of security and the development of trade. Foreign merchants once more flocked to the Port; they settled in the City and became Londoners. The defeat of Swegen and Olaf, and afterwards of Cnut, clearly proves that the citizens were strong enough to beat off a very large and powerful army. This fact is alone sufficient to prove that the City contained a population enormous for the period. In the twelfth century FitzStephen says that London could furnish 60,000 fighting men—a manifest exaggeration. In Domesday Book, prepared after the devastating wars of William, and with the omission of some counties and many towns, we arrive at a population of a million and a half. If we allow for London an eighth part of the population of the whole country, we have 187,500. For other reasons (see p. 190), I think that the population of London at the beginning of the eleventh century was probably about 100,000.

There are many other things about the City of King Edward which we should like to know. Among them are: the procedure at a folkmote; the exact procedure in the trial of a person charged with an offence; the real extent of the power exercised by the Church, e.g. those penances so freely imposed, were they laid upon all citizens or only upon certain persons more devout than the rest? What kind of education was given to the boys and girls of the lower classes? Again, one would like to know what was the position and what the work of a slave in London. Outside London, Domesday Book records 26,500 slaves in all; but in London itself nothing is known about their number. Taking the population of London as one-eighth that of the whole country, the number of slaves would be about 3300. Since there is no trade which has ever been held in contempt by the working classes of London, it is probable that there was no trade specially set apart for the slaves.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content